I can’t for the life of me figure out what ‘UN condemnation’ means. Much more importantly, for the life of Syrians, they probably can’t figure out what it means either. Their lives, after all, hang in the balance of that question.

I know what condemnation means. I know that it’s the noun form of the verb ‘condemn’, which the Mirriam-Webster Dictionary tells us is: 1) to declare to be reprehensible, wrong, or evil usually after weighing evidence and without reservation, 2) to pronounce guilty, 3) to adjudge unfit for use or consumption (condemn an old apartment building), and 4) to declare convertible to public use under the right of eminent domain.

Fair enough.

I also know what the UN is: A multinational organization that can never seem to remember where it hung its good trousers on mornings when there is an early start at the office.

I’m going to guess that in the context of the UN and Syria — although declaring the country ‘public domain’ is desirable — the fourth dictionary definition may be a bit too literal. The third definition makes much more sense from the Syrian perspective, in that they have ‘adjudged’ their government to be ‘unfit for use’. Still, I doubt this is what ‘UN condemnation’ means. That leaves the first two definitions, which have scary-sounding words like, ‘reprehensible’, ‘evil’, and ‘guilty’. Words that have severe tones but don’t really say anything about any actual action, aside from the declaration itself.

This is interesting because ‘condemnation’ has figured heavily in the UN’s lexicon for many, many decades. Archived news articles finds that in ’56 the US wanted the UN to condemn the Soviets for doing bad things in Hungary. In ’61 the Soviets, in a stroke of originality, wanted the UN to condemn the US for doing bad things in Latin America. In ’74 the Brits wanted the UN to condemn the Greek Junta in Greece. In 1990 France asked the UN to condemn Iraq for acting like Iraq in the 80s. The list goes on and on of countries asking the UN to condemn other countries. It seems like the UN has been handing out condemnations like candy at the doctor’s office, and I still don’t know what it means. Or, more to the point: what difference does it make?

Going back to the archives, very little happens after the UN condemns someone. Sometimes there is some diplomatic reshuffling, other times there is a verbal backlash from the condemned. Sometimes there are sanctions — but sometimes there are sanctions even when the UN doesn’t condemn someone. Occasionally, as with Israel in ’74, the condemned country simply ignores the condemnation by the UN and continues doing whatever it is they’re not supposed to be doing. For example, the US keeps embargoing Cuba, the UN keeps condemning it, yet the US keeps embargoing Cuba.

This, to me, is like the staff at a school getting together and deciding that someone is a bully, and then going up to that bully, and saying, “The staff and I have talked, and many of us agree that you are a bully.”

Upon hearing that, even the bully would have a feeling of anti-climax. Especially if he knew how long the discussion amongst the staff went on for. In the case of Syria, the UN, upon pressure from the EU, was figuring on condemning Assad and his heavy-handed treatment of protestors in mid-April of last year. The UN did not actually get around to doing it until the middle of last month — almost a year later. The final resolution, which is not legally binding, was stymied by countries like Russia and China: they condemned the condemnation for tinkering with sovereignty when a political solution is preferable. What that ‘political solution’ could be was illustrated by both countries sending special envoys to Damascus to have tea with Assad.

I have been repeatedly reminded by UN spokespeople that the UN is not a world government. It is merely an organizational body made up of delegates from actual governments and only allows itself to make policy suggestions not laws. Which is fine in terms of protecting national sovereignty, but doesn’t address the problem that arises when that sovereignty is not protecting itself. It’s not fine when it acts like an overweight, sheepish body, stuck in the turnstile leading to the metro during peak time. Until recently The League of Arab Nations has found itself caught behind the UN while it tries to shove through a resolution which attempted to tackle the situation in Syria. I can only imagine which tenuous multi-lateral relationships with UN members kept them from simply throwing their hands in the air and moving on Syria themselves.

I get the impression that if you dropped a pound of wet noodles on the ground and examined it, you would have a fairly good understanding of how countries are related to each other in the UN.

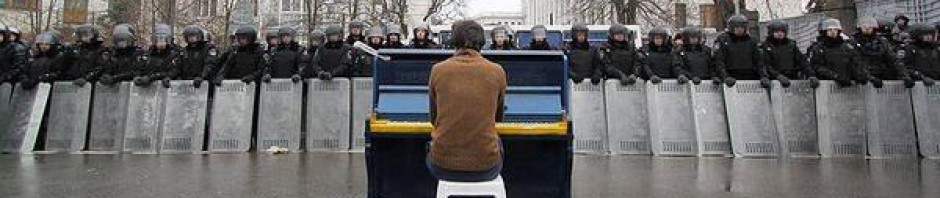

And therein lies the crux of the problem: Nothing stops action like a solid wall of political bureaucracy. And there is nothing quite as politically bureaucratic as the UN. It is, after all, the sum total of nearly 200 member states, each trying to sort out its own pile of wet noodles.

So, as the reports of the ‘shelling’ of Homs turn into words like ‘slaughter’ and ‘devastation’ by the mainstream media, the ghosts that haunt the halls of the UN begin shrieking louder and louder. So loud that those earpieces that UN diplomats wear can barely able block out the racket. Ghosts like Rwanda, Kosovo, and Sudan, which have all been condemned in one way or another by the UN, but became ‘slaughter’ and ‘devastation’ regardless. Which may, in fact, go a long way in explaining the earpieces to begin with. Either way, it definitely explains why the UN needs clean trousers every morning.

http://emajmagazine.com/2012/03/10/un-condemnation-what-does-it-mean/