Ever feel grateful for the simplicity of going to the bathroom?

I do.

Not too long ago, going to the bathroom required about 10 minutes of prep beforehand and another 10 minutes de-prep afterwards. The average trip took about 30 minutes, which is a significant chunk of your day. Think about it, you can watch an entire news program in that time. Bank transactions, trips across entire cities, coordinated terrorist attacks and sex have happened in less time. In my case, I had successfully achieved enough of a semi-seated position to make an entry into the human logbook.

That’s life when your leg is fixed in an extended position, in a knee brace you can’t take off. A trip to the bathroom turns into a lunar mission, complete with all the technical and physical complications of getting in and out of a space suit.

First you have to realize that you have go to the bathroom, which is actually more complicated than you might think. Then, if you’re like me and can barely touch your hip when you bend over, fall back into a seated position and start removing your trousers. They have to come off completely. The reason for this will become clear later. Taking off your trousers with my level of non-flexibility is quite complicated when your leg cannot bend. It’s a little like trying to clear your eaves trough without a ladder and no access to the roof.

A previously unappreciated benefit of having a tiny bathroom – toilet and shower ensemble — crammed into a space roughly the size of a telephone booth — is that the toilet bowl is almost directly under the door frame. Looking at my bathroom from the outside makes you think the toilet bowl is semi-successfully making an escape out of the room.

The door frame and the toilet positioning means that I have something to hang on to as I lower myself onto the seat of the bowl. Having a leg sticking straight out means taking a seat is never just taking a seat. It’s a backwards trust fall onto things not used to taking that amount of impact. Trying to do that on a toilet without the benefit of the door frame to hang on to could easily have the same effect as dropping a grenade into a thick, white porcelain vase.

But, before all that, I need to position a chair in front of the toilet in order to keep my straight leg elevated. Why, you may ask, is that a necessity? Well, try sitting on a toilet with your legs straight out, heels sitting resting on the floor in front of you. Think about the amount of available clearance space that allows. Think about the clean-up afterwards. Think about the quality of the product when you’re trying badly to be a vegetarian.

The leg needs to be up. And pulling the foldable chair over in the confined space of the corridor outside my bathroom while balanced on crutches is like trying to dig up potatoes with two five-foot chopsticks.

All right, chair in in position, crutches are within reach, you turn the 180°, grab the door frame with both hands and lower yourself while swinging your leg up and over the chair so that you and your leg land on their respective seats at roughly the same time.

Then you realize your underwear are still on.

All right, not such a big problem. Luckily, unlike trousers, you don’t need to take them entirely off to ahieve the position you need to complete your duties. You still have a knee that actually bends on the other leg. You can, with a bit of aggression, get your limb up and out of one leg hole to leave the remainder of your underwear hanging limply on your outstretched leg like the downed flag of a country invaded by a particularly savage army.

And, of course, half the time, you went through that entire effort only to realize that you just needed to fart.

It took a while to finesse a technique to get my trousers back on again. Hell, it took a while to finesse trimming the toenails on my left foot. Having no flexibility whatsoever to begin with means I can’t reach the floor, let along my feet, without bending both knees. And if one knee can’t bend in these situations, the other might as well not be able to as well. This all makes pulling trousers on fairly difficult.

Before I found a better way, I’d sit and kind of throw my trousers at my left foot in the hopes that the waist would land around it, like the world’s shittiest game of horseshoe. Eventually, after usually no less than five tries, I’d get the trousers over my foot and from there, use the foot of my good leg to manoeuvre the garment over the leg brace and further up my bad leg. I had to get them high enough to for me to reach the waist of my trousers with my outstretched fingers to pull them up a bit more. Then I was squirming around on my back to get my good leg in the correct hole and pull it all the way up. Again, astronautical amounts of effort for what used to be a simple task.

The leg brace, by the way, was secured to my leg with about five thick, tough velcro straps and adjustable hinges on either side that stuck out like the bolts on the Frankenstein monster’s neck. For a months after my knee injury — that fucked up day in Washington DC — the adjustable hinges were fixed in ‘wrought iron fence post’ straight position. Trying to pull trousers over the brace was like trying to pull a dress sock over a bulldozer.

Eventually, though, I figured out that if I pass my belt through one belt loop of the trousers and then threw them at my feet while hanging on to either end of the belt, I’d given myself about a foot of arm length to play with in terms of pulling on my trousers.

Genius.

I also figured out that if I duct tape my nail-clippers to the floor, manoeuvre each toe into the six millimetre opening of it’s stainless steel mouth, and use my crutch to press down on the clipper’s lever like a hole punch, I could very badly trim the nails on the toes of my left foot in about an hour.

Also genius.

I suppose it would have been easier to hire someone to help, but trying to get my insurance company to pay for anything is the kind of frustrating bureaucratic fuckaround you’d probably have trying open a ‘Bed Bath & Beyond’ in Mogadishu. Besides, the prospect of a stranger being in my house, helping me go to the bathroom, shower and clip my nails, was not something I could stomach.

If you’ve ever been to a typical Dutch house you’ll know that you basically need rappelling gear and ice picks to get up and down the stairs — even living on the second floor afforded no easy exit from my flat. Of course, every two weeks I’d have to leave to make a trip to the hospital. This required my entire body and full concentration. At the beginning, it was “sitting” my way down the stairs. A noisy operation that involved me sitting on every step on the way down, while trying to keep my crutches with me. Usually, when I braced my hands against the steps to lower myself one more step down, the crutches would attempt an escape, clattering down the flight of steps, making my upstairs neighbour think people were attacking each other with hammers in a tin hall outside their doors.

It also meant I could not venture out with anything more than my crutches and my satchel which hung across my shoulders. I definitely couldn’t take garbage out, and there was absolutely no way to bring supplies like groceries and toilet-rolls in.

For the garbage and recycling, I relied on friends. For the groceries, I figured out that Albert Heijn (a Dutch supermarket chain) will deliver all the way into your kitchen. Budgeting for grocery delivery had me eating a very specific diet for three months:

Breakfast:

Banana and orange

Lunch:

Two slices of bread, one with aged goat cheese, the other with peanut butter

Snack:

Cherry tomatoes, baby carrots, hummus, peanuts

Dinner:

Microwaved veggie burger between two slices of bread with mayo and a side of potato chips.

To mix things up I’d switch up the flavour of the chips.

My beverages were vast quantities of water, coconut water, lactose-free milk and Leffe beer.

In hindsight, I suppose being effectively trapped in my flat and having a very repetitive diet was bit like being locked in a minimum security prison with a moderately better view, nicer ambient noise and less rape. It’s hard to say whether or not I went bonkers with all the isolation and limited movement. My friends who saw me may insist otherwise, but as an only child I may have been better equipped than most to handle entertaining myself during the weekends and long, empty hours after work.

It would be great to say that I used the time to read good books, compose guitar music, paint, write a novel or even keep a memoir of my situation, but I didn’t. I watched lots and lots of TV and films. I figured, I’m living with my fucking condition, why would I want to write about it?

Even now, almost a year later, I’m living with it, but to a far, far lesser degree. For example, Getting up from the floor is a huge hassle without anything to grab on to. I’m basically the American flagpole at Iwo Jima, requiring the remnants of a broken American platoon to get me upright. I try to not spend too much time on floors.

But whereas I could actually get up now, at the height of my incapacitation, even getting down — without face-planting, or executing an inelegant, backwards, Jesus-on-the-cross flop — was impossible.

That being said, the growing distance between then and now is making memories grow dimmer, and with it, the recall of day-to-day life from August to November of 2017… aside from the incident itself and what immediately followed. That millisecond moment that exploded my daily routine is branded into my mind for good. A massive checkered flag planted firmly in my life, like my first kiss, 9-11, or The Challenger disaster (not necessarily in that order).

I’ve often tried to come up with a way to describe the pain, and when I do, I relive it. Which is not what I want to do. Ever. Again. I’ve found myself backpedalling describing it to women who have had a kid. Giving birth, I’m told, is like crapping out a Fabregé Egg, or passing a wheat harvester through your urethra, or getting your crotch beaten by ten pneumatic sledgehammers, or other analogies. Whatever, all I know is that you do not want to get into a relative-levels-of-pain-experienced fire fight with a women who’s had a kid. Wait for the second kid.

How do you describe the very subjective concept of personal physical pain? It’s a weird thing having something so easily remembered and so difficult to describe.

There was a pop sensation. A jack-knife spike of pain that I felt viscerally. Like a starting-gun going off for things to come.

I had been invited to play softball — softball, a game for children and the infirm — by Greenpeace US against the Amnesty US in Washington, DC. We were going to play on the National Mall in DC. You know “The Mall”, it’s been in any film or TV show which features anything happening in the US government. Martin Luther King spoke about his dream over it, and Forrest Gump ran through it. I was going to play a national pastime near a international icon. Hell yeah, I’ll play.

Perhaps it was the running shoes, good only for running on a track. I had actually intended on jogging around the mall like a character from the West Wing. It was hot and humid outside, so there was a layer of dew everywhere and we weren’t on a proper sand baseball diamond. Basically, without cleats, you had about as much grip as silk sandals on ice. Maybe it was the rotation of my body on the swing. Maybe it was the act of planting my left leg and pushing off to make a run for first base. Maybe it was all of it, or maybe it was none of it.

All I know is that on my very first time at any plate in about 20 years, on my very first swing, with my very first connect with the ball, the knee cap of my left leg popped off and slid under the skin to the left side of my knee.

Of course I didn’t know that’s what happened at the time. I think I thought I just wiped out. Except for the pop and the rapidly cohesive knowledge that something was very, very wrong.

The kneecap is fixed in place over a socket by a tough and taught bit of sinew called the patellar tendon. It’s egg-coloured and has the strength and tight tenacity of the fan belt on a car engine. It runs from that big meaty muscle at the top of your thigh called the quadriceps over the patella — your kneecap — and attaches to the top of your shin bone— tibia. In the highly unlikely event that the patella pops to the side of the knee, the tendon moves with it, and all that brute tension that crosses the knee, suddenly jerked to the side of your joint, now pulls your ankle towards your ass.

Lying there on my back I was aware of three things: a pain so extraordinary it caused my brain to careen wildly between processing the agony and trying to figure out what the fuck had just happened, the sensation of feeling my knee cap where it wasn’t supposed to be with my left hand, and laughter.

Objectively speaking it probably looked hilarious. I essentially swung a bat, hit a ball and then collapsed to the ground like I’d been tazed. A middle-aged, out of shape dude, who used up all his energy in a single swing. I was vaguely aware of people wandering over, probably thinking I was doing the hammy fish-on-land flip-flop that professional footballers do when a breeze knocks them down.

I was acutely in need of relief from the pain and the ping-pong mental processing of the unnatural feeling of the position of my leg. Eventually it crystalized in my mind that the only respite was to get my leg straight again. Oddly, a quite lucid internal voice said, “That may be what you think will help, but you’re no doctor.” Or maybe I said something out loud and that was the response from someone in the crowd gathering around me.

I couldn’t straighten my leg though. The relentless tension created by the position of my patellar tendon wouldn’t allow it. Also, I was aware that I was starting to pass out — the edges of my peripheral vision were getting fuzzy. So, using my right foot I kicked my left leg straight and rammed my kneecap back into its groove.

Relief!

But not a lot. I could feel the knee cap would snap out of position again if I tried to bend my leg. And I was getting very dizzy. I needed to concentrate on a task. A task like self-care. I needed a splint – something to keep the leg straight. I looked around the field. Between gasps I asked for someone to bring me one of the baseball bats. Something to secure the bat… something to secure the bat. Belts! I need belts. The NGOers gave me belts.

I lashed the baseball bat to my leg above and below the knee. Likely numb due to shock I somehow got it into my head that things were fine — that I could uber to a hospital. With that in mind a few folks got behind me to hoist me up.

Pop.

The kneecap snapped out of place again. Jesus. Jesus, put me down, put me down.

Thankfully the splint kept the leg relatively straight, so shoving the knee cap home was easier. As I was tightening the splint I realized that I would need an ambulance.

Aside from bottom-feeding accident claim lawyers and chronic hypochondriacs, who really wants to ride in an ambulance? Not only was I aware that in the US I’d probably have to donate a kidney to afford an ambulance ride to the nearest hospital, but there is something supremely undignified about being the recipient of emergency medical response care. Like you’ve so totally and helplessly lost control of your personal situation that it requires the arrival of a loud disco-lit truck and a team of people with invasive contraptions to put things back in order. After watching the ambulance drive around the park for about ten minutes as it tried to find an access route to where we were in the park, I was hoisted onto a gurney, baseball bat splint and all, and the gurney was shoved unceremoniously into the ambulance.

The person who had invited me to play softball in the first place rode with me. She felt awful. I told her it was my choice to play, and to not feel bad as I clung to my kneecap, refusing to let go out of fear of it making a dash for it, like a vole under a sheet cover.

Hospitals are horrible places, and the George Washington Memorial was no different. I was told to fill out a stack of forms and liability documents in case I died in the process of them doing whatever it is they needed to do to my knee. Which, as it turned out, was not much.

The form of care looked like this.

I was parked in curtained-off room while my travelling companion started trying to sort out traveller’s health insurance on her phone. Eventually she said, hey, I think you may have this, and showed me a Wikipedia a page called “patellar luxation”. After that a few folks in white lab coats would occasionally stick their head through the curtain, stare at my leg without approaching it and then leave. I believe word got around the hospital that someone had been wheeled in wearing a baseball bat for a splint and people were checking out my act for themselves. Somewhere along the way I was given morphine. At one point, I’m proud to say, one doctor — who could also have easily been a janitor for all I know, I was so high — said my splint was exactly the right thing to do. Then my travelling companion told me an extremely vivid story about her trip to the museum of African American History. Then I was x-rayed. An orderly came and put a brace around my leg to keep it straight then a doctor arrived. He told me he thought I had a patellar luxation and handed me a print-out of the exact same Wikipedia page I had been shown three hours earlier by my travelling companion. The doctor also told me to give it about six days and I should be fine.

This mind-boggling level of high-end, privatized, expert American medical treatment cost me 777 USD. I would later be charged an additional 2000 USD for the ambulance ride. Also, because I was a foreigner, they wouldn’t let me leave the hospital until I paid. And the longer I stayed in the hospital the more they would charge me. It was like being stuck inside an Escher painting that smelled of disinfectant. People have said this far more eloquently than myself, but after having actually lived through it, it bears repeating: The US medical system is fucking retarded.

After some idiocy with my credit card limit I paid and left with a pair of crutches, a knee brace and the realization that the coming days were going to be absolute shit.

Also, they didn’t secure the brace well enough. When I got back to my hotel room, where I would spend the rest of the week, I tried to sit on the bed. Pop.

You’d think that I would be an expert at dealing with that level of pain at this point. But the morphine had worn off and as I, again, kicked my leg out and popped my kneecap back into place, I started sweating profusely and seeing stars.

The rest of the stay in the hotel room in DC was a dull-as-cardboard repetition of over-the-counter pain-killers, water, ice and Oreo cookies, all delivered by very fine colleagues. I watched a steady stream of art documentaries on YouTube while drifting in and out of sleep. This was punctuated by moments of raw rage at my condition and replacing the ice pack. I was afraid of moving at all — so I really didn’t move, maintaining the exact same semi-reclined hospital bed position, even in sleep — for about four days, out of fear of dislocating my knee again.

I did manage to do a wet-towel cleaning of my body once, seated on the bathroom floor of the hotel suite, my leg extended straight out on a bunch of towels I threw down. They had affixed the leg brace over the jogging pants I wore and it was starting to offend anyone that came to visit me to drop off more pain killers, Oreos and water.

I was just waiting to get home. And that day did eventually come.

But not before my knee cap popped out again while trying to get some trousers on. This time I screamed. It wasn’t just about feeling like my knee was being smashed between two bricks, it was frustration at being lulled into a false sense of improvement because of my immobility the previous four days. The roar of anger, frustration and pain was enough for someone to knock worriedly on the hotel room door and ask, “Is everything okay?” with the same tone you’d use to address any closed hotel room door in Washington DC behind which you’d heard a scream.

They had to order a Ford escalade, basically an urban tank, to get me to the airport because I could no longer fit normally into a car. I had to be able to sit across the backseat bench, my back against the passenger window and have my crutches with me. This would continue to be a hard thing to explain to any taxi service I’d need the following months. It also meant that my jogging-pants pocket was well positioned enough for my mobile phone to fall out and travel back to DC without me.

I didn’t realize that little pearl until I reached for it at the airport to indicate that I’d been re-booked onto a first class flight back to Amsterdam. Which sounds better than it is after you’ve considered the practicalities of trying to fit me anywhere on a flight, besides the aisles and the cargo hold. As it stands, even without dragging around a large and useless limb, I can’t fit into airplane seats.

Or wheelchairs either, it turns out. Apparently it is airport policy that people at a certain, slightly arbitrary, level of diminished physical capacity must be wheeled around in a wheelchair. The problem is, wheelchairs are not designed for someone whose leg doesn’t bend. Not unless you’re trying to create forward momentum to catapult them over a fence by using the outstretched leg as a vaulting pole. I ended up sitting with one ass cheek on the armpit end of the crutch with the business end sticking straight out so that I could rest my leg fully outstretched. The whole setup looked like a wheeled joust machine designed in an orthopaedics’ lab.

In Schiphol airport in Amsterdam I was met by the tiniest airport staffer I’d ever seen. She had been designated to wheel me and my suitcase. You could probably have fit two of her into my suitcase.

Christ, talk about feeling guilt at having this poor little human struggling to push me with one hand and pull my suitcase with the other. We both learned that because of my long horizontal length we both couldn’t fit in the elevator. She’d have to position me to maximize the diagonal width and use the tiny remaining room around me to fit my suitcase. This took a few tries and all had to be done with the elevator door constantly wanting to close as people in the floor below hammered on the lift button and cursed it’s lack of arrival. She’d also have to race to the nearest stairs and down a floor to be able to meet me when the elevator door opened again.

Throughout all of this she remained upbeat. Between gasps of air at the effort of wheeling me and my stuff a fairly great distance she did her best to try to maintain light banter. It was an impressive display of personal fortitude, patience and sheer, brute strength.

In many ways I’m grateful that my travel insurance was based in the Netherlands. Things just work here. Although they couldn’t pay off my medical fee at that moment they sorted out my flight back to Schiphol, tiny airport attendant in Amsterdam and very large cab back to my flat.

I’m still a little dubious about the orthopaedic health care I received. I’d never heard of my kind of injury until it happened to me. I had and have no basis of reference aside from what I’d read online – which in and of itself wasn’t very helpful. Recovery time, for instance, could take between one week and two years. Treatment was anything from a compression sock and re-hydration, to replacing the entire leg with one that works.

Before even getting to the point of seeing an expert I needed to hobble, on crutches to the nearby general practitioners office to get a referral. This involved, again, getting in and out of a cab, which, if I were a few inches taller would have required me having to stick my leg out the passenger side window like a surfboard in Malibu.

Nothing actually happened at the GP’s. I turned up, she said, what’s wrong, I said, patellar luxation, she said, okay, we’ll get back to you with some specialists you can go to. I turned around with the grace and speed of an aircraft carrier and hobbled back to the car park. About two days later I got a call from someone at my GP’s office asking me if I wanted a meeting with an orthopaedic surgeon in “two weeks or in one month”.

I said, I want to see one right now. I explained that I’d rather not be stuck like this; unsure if my kneecap is actually where it’s supposed to be, unsure if all the continuous swelling is supposed to happen, unsure if I’m healing correctly or at all, with no idea what the treatment is or when the leg brace can come off (you fucking idiot)…

And, as always happens in the Netherlands, she had low-balled me at first with the least convenient option, forcing me to haggle like I was in a Kasbah stable trying to buy a camel. It turned out, that an orthopaedic surgeon could see me the next day.

My treatment felt a little absentee-fatherish. I saw the orthopaedic surgeon twice in about seven trips to the hospital; the first and last trip. The three other times I saw any doctor it was his trainee who appeared to be about 14 year-old. The kid had zero sense of humour and an expression like he was suppressing a gag reflex whenever he came within a few feet of a human. A splendid quality for a health care professional. And there’s nothing quite like that moment in life when suddenly the doctors — the people who you empower to handle your health — are younger than you.

The orthopaedic surgeon strode into examination room and I suddenly got the uneasy sense of being in a small space with a sociopath. He probably wasn’t, but there was a cool detachment which I found a bit unnerving. He looked at the knee and said that he couldn’t really tell what the situation was, but that I should start doing physio, get an MRI and head to the “mechanic” (loose Dutch translation) to get fitted with a new knee brace. The logic was that every two weeks I’d return to the hospital and the mechanic would adjust the hinges of the brace to allow for another 30° of knee bend.

All well and good, except when I went to the physio she stared blankly at my knee and said, we can’t build the muscles around your knee if you can’t take off the brace to bend your knee. The MRI resulted in nothing clear except for providing me with what I thought was a hilarious social media post. The 30°-every-two-weeks scheme didn’t work in a way that made it seem a bit ad hoc.

Trips anywhere fell to “my driver” who was actually just a guy with a big taxi who I got into the habit of calling. He was into some kind of L. Ron Hubbard style new wave religion thing and had a tad too much affection for the Third Riech. He had a tendency to tell me about the interconnected of everything and the things he thought the Nazis got right. Genocide was not one of them.

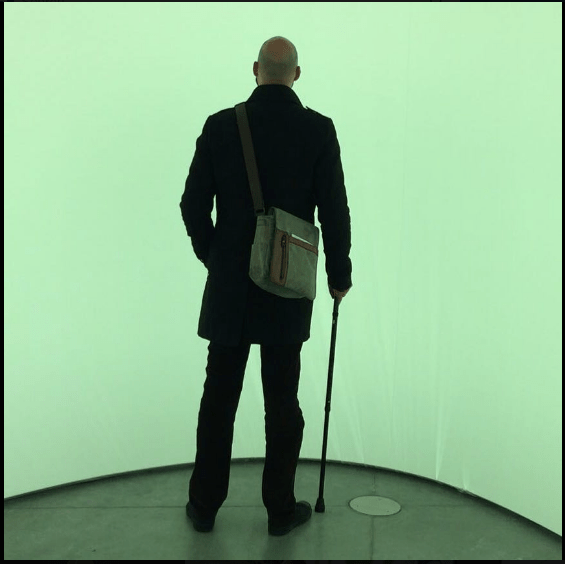

The most significant medical breakthroughs and personal steps (ha) forward had nothing to do with the doctors. The place where the magic happened was at the mechanic’s. At first I was a bit sceptical of a guy with no medical degree telling me, after about six weeks weeks, to try to take a few steps without the crutch. I would try, very gingerly, and holy hell! I could! The leg muscles had atrophied quite a bit, but I had bought a cane to help me along. Before that he had encouraged me to only use one crutch, which turned out to work as well to my happiness and shock. The man was like Jesus to me.

He also gave me what could only be described as a massive condom to fit over the brace for taking a shower. Getting the thing on was similar to getting my trousers on — horse shoe lobbing the things at my feet until it caught, and then using the crutch to manoeuvre it up and over the brace. For washing the offending leg I’d have to sit on the floor of my tiny bathroom, the leg outstretched, now beneath the toilet bowl, take the brace off and wet-towel the limb. I still can’t remember how I managed to get to a standing position, except it had something to do with nearly wrenching the toilet bowl out of its fixings.

The scheme of adding an extra 30° bend to my brace every two weeks may not have worked as intended. When the brace finally allowed for that level of flexibility, I still could only bend it about 75°. Apparently my tendons and muscles had spent so much time in an extended position, they thought that was the new normal state of affairs. I still can’t get past about 130° so engaging in prayer in many religions is out of the question.

Medical equipment is a bit vulgar-looking, and the cream-coloured aluminium crutches were no different. They just looked ugly. They always had to be within reach and they were always falling down, making the kind of noise you’d get dropping a sack of tin cans into an aluminium bin.

I was dropping things more during that time. I know, because picking anything up from the ground required massive amounts of effort. It was par for the course when you’re trying to transport stuff from one room to room in a tiny flat with both hands occupied by crutches. When something fell to the floor I’d fly into a rage at a level usually associated with violent religious zeal. My neighbours must have heard my roars, but were too polite to say anything when they saw me months later wielding a cane.

Aside from trips to the hospital, exposure to the outside world was extremely limited. Occasionally I’d stand at the window, supported by crutches, and stare at the road and the apartment across the street like Jimmy Stewart in Rear Window. I actually went on a couple dates with someone. She insisted my immobility and big, dumb crutches wasn’t an issue, but texted me that she was leaving the country when, after a brief period of non-contact, I asked her if we were going to hang out again.

I figure I dodged a bullet there. I actually dodged another one when I had to break a promise to be there for an ex who was giving birth. Dodging bullets is not a skill you’d normally associate with a guy with the mobility of a stop sign.

The transfer from crutches, to one crutch, to cane was an interesting one. It was like moving from the high school yearbook committee to president in five months. Where I was a clunky, stumbling mantis-shaped human with crutches before, with the cane I was an 18th century aristocrat explorer, freshly returned home. Everyone, including complete strangers, wanted to talk to me. I was given premium service in airports, and, when I was anywhere other than the Netherlands, offered a seat on public transportation.

Moments of progression came as surprises, and usually far outside of my comfort zone. Against my paranoid judgement I ended up going to Norway in November for work; managing to deal with the ice and long wanders for work and museum visits.

It wasn’t long after the cane days when I hiked a rat-bastard of a rocky trail up a mountain on Lantau Island in Hong Kong. This wasn’t planned and the fear of my kneecap popping off — rendering me immobile on a remote path on the opposite side of the world — constantly loomed, like a gun shot injury at a rifle show.

The fear of another patellar luxation — another pop — is probably not dissimilar to suffering from PTSD. That injury must never happen again. At any cost. The orthopaedic surgeon saying that for 60 to 70% of people it never happens again does not inspire confidence. Surgery was an option, if I insisted, but I didn’t because the prospect of spending another three months in locked-down, motionless recovery made me want to stick my head in a man-of-war jellyfish aquarium.

This is probably why my physiotherapists are gently trying to tell me to fuck off. They understand the fear and want me to trust my knee more and not waste their valuable time when they have people with real injuries who actually need them.

After all, I’d set my goal at the beginning of the physio sessions: to achieve riding a bike again, and, eventually, jog. I can and have been riding to work and everywhere, and I can almost jog again. That being said, I won’t be competing in any MMA matches.

I used to take stair steps two at a time and now I can only take them one at a time. And I still try to avoid being on floors as much as possible.

Just read the blogpost,love the way you write! Anyway I’m going for a knee surgery as well have been reading this blog https://www.kneepainremedy.com and was wondering if your experience was the same?